Cairo greeted me with the same intensity I remembered—alive with history, movement, and meaning. Returning after 24 years, I stepped back into a city that shaped my youth and found it as captivating and multilayered as ever.

Cairo is a living museum—a sprawling metropolis where millennia-old monuments stand alongside modern high-rises, where the call to prayer echoes over honking traffic, and where every corner tells a story. My first encounter with this mesmerizing city was in 1993, when I spent a summer working at the National Bank of Egypt (NBE) as a university student. That experience left an indelible mark, and though it took me 24 years to return, stepping back into Cairo’s vibrant streets felt like reconnecting with an old friend.

Reconnecting with the past: An evening in historic Cairo

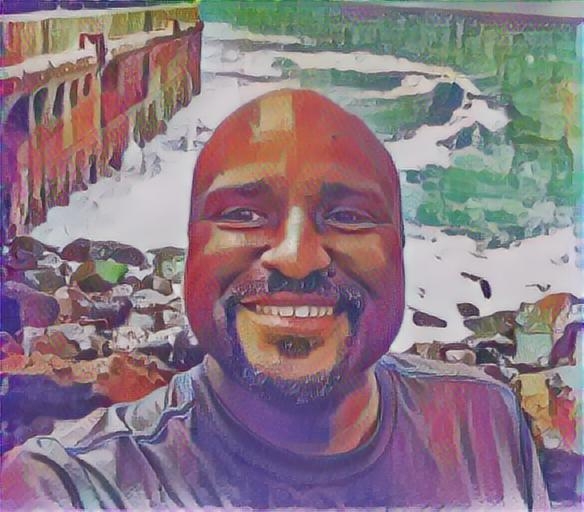

One of the highlights of my return in 2017 was reuniting with Abdel Moneim, a former colleague from my summer experience at the NBE. When we last met, I was a wide-eyed student and intern, and he was a young professional starting out his career; now, he was a retired senior executive. He warmly greeted me outside the Semiramis Hotel, accompanied by his adult daughter, a poised young woman who hadn’t even been born when I left Cairo in 1993.

|

Reuniting with my dear friend Abdel Moneim and meeting his daughter in Cairo (2017). Reuniting with my dear friend Abdel Moneim and meeting his daughter in Cairo (2017). |

Abdel Moneim and his daughter insisted on showing me their Cairo by night, and our tour became a masterclass in the city’s layered history.

Islamic Cairo: A living architectural museum

We began in Islamic Cairo, where medieval mosques and madrasas glow under golden illumination after sunset. The Mosque-Madrassa of Sultan Hassan, a 14th-century Mamluk masterpiece, left me speechless with its towering portal and intricate arabesque carvings. Nearby, the Al-Rifa'i Mosque—where Egypt’s last kings are buried—showcases Ottoman grandeur with its domed ceilings and gilded details.

Walking through Al-Muizz Street, one of the oldest roads in Cairo, felt like stepping into an open-air museum of Islamic architecture. The ornate wooden latticework (mashrabiya) on historic houses and the delicate stucco patterns on mosque walls are testaments to the artisanship of Egypt’s golden age.

Coptic Cairo: Where Christianity took root

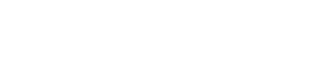

Next, we ventured into Coptic Cairo, the heart of Egypt’s Christian heritage. The Hanging Church, suspended over Roman-era gateways, is a marvel of early Coptic design, with its ivory-inlaid screens and ancient icons. Nearby, the Church of St. Sergius and Bacchus is believed to have sheltered the Holy Family during their flight into Egypt.

The Coptic Museum's collection of early Christian textiles and manuscripts helped me appreciate how this neighbourhood preserves faith traditions dating back to the 1st century AD.

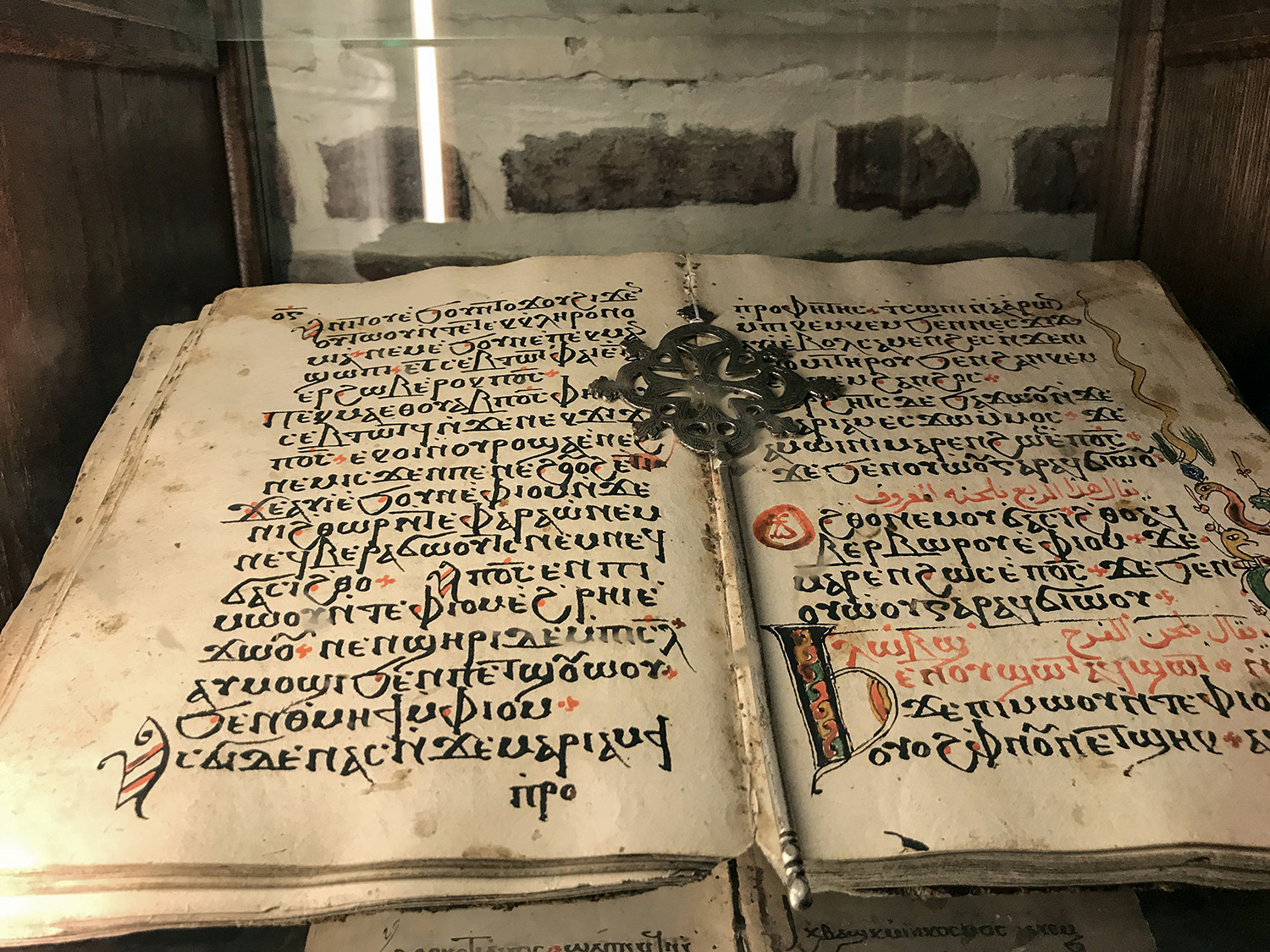

Khan El Khalili: A sensory overload

No night in Cairo is complete without losing yourself in Khan El Khalili, the legendary bazaar that has thrived since the 14th century. The scent of cardamom coffee and shisha tobacco filled the air as we wove through narrow alleys lined with brass lanterns, handwoven carpets, and glittering jewelry stalls. Abdel Moneim’s daughter laughed as I haggled (badly) for a silver scarab pendant—proof that some skills fade with time.

We paused for a meal and enjoyed each other's company over plates of koshari (a hearty mix of lentils, pasta, and crispy onions), ful medames (slow-cooked fava beans), and molokhia (a garlicky green stew).

As we lingered over sweet mint tea, watching the bazaar's nightly ballet of merchants, locals and wide-eyed tourists, I realized Khan El Khalili isn't just a market - it's a living theatre where Cairo's past and present perform together nightly.

The Pyramids of Giza: Confronting timeless majesty

The next morning, I set out for the Giza Plateau, where the pyramids have stood for over 4,500 years. The last time I visited, in 1993, I had challenged myself to walk all the way to the Giza Plateau from my humble hotel residence near Tahrir Square. Needless to say, the hours-long walk was hot and exhausting. But I remember discovering a lot of the real Cairo along the way. This time, I took a taxi—like a normal and sane person!

Back then, I had walked straight to the Sphinx and the Pyramids as I made my way through stands kept by local villagers. Some of these young villagers could speak multiple European languages as they interacted with tourists. I remember being thoroughly impressed. Things had changed over two decades later. Now, a formal entrance gate and ticket booth mark the shift toward managed tourism.

The Great Pyramid of Khufu

Standing before the Great Pyramid, I felt the same awe as I had decades earlier. The precision of its construction—each limestone block weighing 2.5 tons, fitted without mortar—is a marvel of engineering. Climbing a few steps onto the base, I ran my hand over the weathered stones. The pyramid's perfect square base, aligned with near-perfect cardinal directions, covers 13 acres - equivalent to nearly 10 football fields.

I entered the pyramid's interior, joining the limited number of visitors allowed inside each day. The entrance leads to a narrow, descending passage, but the real experience begins with the Ascending Passage – a tight, 3.5-foot-high corridor that requires crouching while climbing upward at a steep 26-degree angle.

After the challenging climb, the passage opens into the Grand Gallery, a striking 28-foot-high corridor with a corbeled ceiling. The precision of the stonework is remarkable, with massive limestone blocks fitting together seamlessly without mortar. At the top of the gallery lies the King's Chamber, a simple, rectangular room built entirely from red granite. The only object inside is an empty sarcophagus, its purpose still debated by Egyptologists.

The interior is humid and warm, with minimal airflow. While not decorated like later Egyptian tombs, the architectural precision speaks volumes about the builders' skill. The experience is physically demanding—those with mobility issues or claustrophobia should reconsider.

The Sphinx and a camel ride

No matter how many times you’ve seen it in photographs, nothing prepares you for standing before the Great Sphinx in person. The colossal statue—carved from a single limestone outcrop—has watched over the Giza Plateau for nearly 4,500 years, its lion’s body and human face (believed to represent Pharaoh Khafre) radiating quiet authority. Time has worn its features—the nose famously missing, the ceremonial beard now displayed in the British Museum—yet the Sphinx loses none of its power.

Nearby, a chorus of camel drivers called to passing tourists. “Special price for you, my friend!” one grinned, spotting my hesitation. I surrendered—partly for the experience, partly for the perspective.

Clambering onto the camel’s back was its own adventure (tip: lean back sharply when it stands!), but once we set off across the sandy plateau, the view justified every cliché. From this elevated vantage, the three pyramids of Giza aligned perfectly—Khufu’s Great Pyramid looming largest, with Khafre’s (still bearing traces of its original smooth casing stones) and Menkaure’s completing the family tableau.

Was it touristy? Absolutely. But as the pyramids’ shadows stretched long across the desert, their silhouettes softening in the dusk haze, I understood why this ritual endures: for a few quiet minutes, swaying atop a “ship of the desert,” you don’t just see the pyramids—you feel their ancient heartbeat.

Saqqara and Memphis: The roots of Egyptian civilization

As an Egyptology enthusiast, I couldn't be in Cairo without venturing south to Saqqara and Memphis – two sites that reveal the origins of Egyptian civilization long before the Giza pyramids were built.

Saqqara: The birthplace of the pyramid

The Step Pyramid of Djoser (c. 2650 BC) dominates Saqqara's landscape as the world's first large-scale stone structure. Designed by Imhotep – history's first named architect – this revolutionary six-tiered pyramid began as a traditional mastaba (flat-roofed tomb) before being expanded vertically, marking a pivotal moment in architectural innovation.

Walking through the pyramid complex, I admired:

- The Colonnaded Entrance: Rows of ribbed columns designed to resemble bundled reeds, showcasing early stone-carving techniques.

- The Serapeum: An underground network of tunnels containing enormous granite sarcophagi (weighing up to 80 tons) for the burial of sacred Apis bulls. The precision with which these massive boxes were carved and positioned is mind-boggling.

- The Tomb of Ti: One of Saqqara's best-preserved mastabas, featuring vibrant reliefs depicting fishing, farming, and dance scenes from Old Kingdom daily life.

Recent excavations continue to uncover new discoveries at Saqqara, including hundreds of sealed sarcophagi and a 4,400-year-old priest's tomb, named Wahtye. This tomb, dating back to Egypt's Fifth Dynasty, was remarkably well-preserved, featuring vibrant wall paintings and numerous statues depicting Wahtye with his family.

Memphis: Egypt’s first capital

Once the thriving heart of ancient Egypt, Memphis was founded around 3100 BC by Pharaoh Menes, who is credited with unifying Upper and Lower Egypt. As the first capital of a unified kingdom, Memphis quickly rose to become a political, cultural, and religious hub for centuries. Today, little remains of the vast metropolis that once stood, but what survives has been transformed into an evocative open-air museum just south of modern-day Cairo.

The star attraction is undoubtedly the colossal statue of Ramses II. Though it lies on its back, the statue still commands attention with its immense scale and lifelike detail. Carved from limestone and measuring over 10 meters long, the sculpture captures the pharaoh in his prime—muscular, confident, and serene. The craftsmanship is astonishing: the pleated folds of his royal kilt, the precision of the hieroglyphs on his belt, and the subtle curve of his lips reflect the artistic heights reached during the New Kingdom.

A city that endures

Returning to Cairo after 24 years taught me that while cities evolve, their soul remains. The pyramids still inspire wonder, the bazaar still buzzes with life, and friendships—like mine with Abdel Moneim—transcend time.

For first-time visitors, Cairo can feel overwhelming. But lean into the chaos: sip tea with locals, let the call to prayer be your soundtrack, and remember that you’re walking in the footsteps of pharaohs, caliphs, and generations of dreamers.

When to Go: October-April for mild weather.

I won’t wait another 24 years to return. Inshallah, I’ll be back soon.

Comments powered by CComment